1.

Chabon. Obreht. Franzen. McCann. Egan. Brooks. Foer. Lethem. Eggers. Russo.

Possible hosts for Bravo’s America’s Next Top Novelist? Dream hires for the Iowa Writers’ Workshop?

Nope — just the “Murderer’s Row” of advance blurbers featured on the back of Nathan Englander’s new effort, What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank. And what an effort it must be: “Utterly haunting. Like Faulkner [Russo] it tells the tangled truth of life [Chabon], and you can hear Englander’s heart thumping feverishly on every page [Eggers].”

Nope — just the “Murderer’s Row” of advance blurbers featured on the back of Nathan Englander’s new effort, What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank. And what an effort it must be: “Utterly haunting. Like Faulkner [Russo] it tells the tangled truth of life [Chabon], and you can hear Englander’s heart thumping feverishly on every page [Eggers].”

As I marvel at the work of Knopf’s publicity department, I can’t help but feel a little ill. And put off. Who cares? Shouldn’t the back of a book just have a short summary? Isn’t this undignified? But answering these questions responsibly demands more than the reflexive rage of an offended aesthete (Nobody cares! Yes! Yes!). It demands, I think, the level-headed perspective of a blurb-historian…

2.

Let’s be clear: blurbs are not a distinguished genre. In 1936 George Orwell described them as “disgusting tripe,” quoting a particularly odious example from the Sunday Times: “If you can read this book and not shriek with delight, your soul is dead.” He admitted the impossibility of banning reviews, and proposed instead the adoption of a system for grading novels according to classes, “perhaps quite a rigid one,” to assist hapless readers in choosing among countless life-changing masterpieces. More recently Camille Paglia called for an end to the “corrupt practice of advance blurbs,” plagued by “shameless cronyism and grotesque hyperbole.” Even Stephen King, a staunch supporter of blurbs, winces at their “hyperbolic ecstasies” and calls for sincerity on the part of blurbers.

The excesses and scandals of contemporary blurbing, book and otherwise, are well-documented. William F. Buckley relates how publishers provided him with sample blurb templates: “(1) I was stunned by the power of [ ]. This book will change your life. Or, (2) [ ] expresses an emotional depth that moves me beyond anything I have experienced in a book.” Overwrought praise for David Grossman’s To the End of the Land inspired The Guardian to hold a satirical Dan Brown blurbing competition. My personal favorite? In 2000, Sony Pictures invented one David Manning of the Ridgefield Press to blurb some of its stinkers. When Newsweek exposed the fraud a year later, moviegoers brought a class action lawsuit on behalf of those duped into seeing Hollow Man, The Animal, The Patriot, or Vertical Limit (Manning on Hollow Man: “One hell of a ride!” — evidently moviegoers are easy marks).

The excesses and scandals of contemporary blurbing, book and otherwise, are well-documented. William F. Buckley relates how publishers provided him with sample blurb templates: “(1) I was stunned by the power of [ ]. This book will change your life. Or, (2) [ ] expresses an emotional depth that moves me beyond anything I have experienced in a book.” Overwrought praise for David Grossman’s To the End of the Land inspired The Guardian to hold a satirical Dan Brown blurbing competition. My personal favorite? In 2000, Sony Pictures invented one David Manning of the Ridgefield Press to blurb some of its stinkers. When Newsweek exposed the fraud a year later, moviegoers brought a class action lawsuit on behalf of those duped into seeing Hollow Man, The Animal, The Patriot, or Vertical Limit (Manning on Hollow Man: “One hell of a ride!” — evidently moviegoers are easy marks).

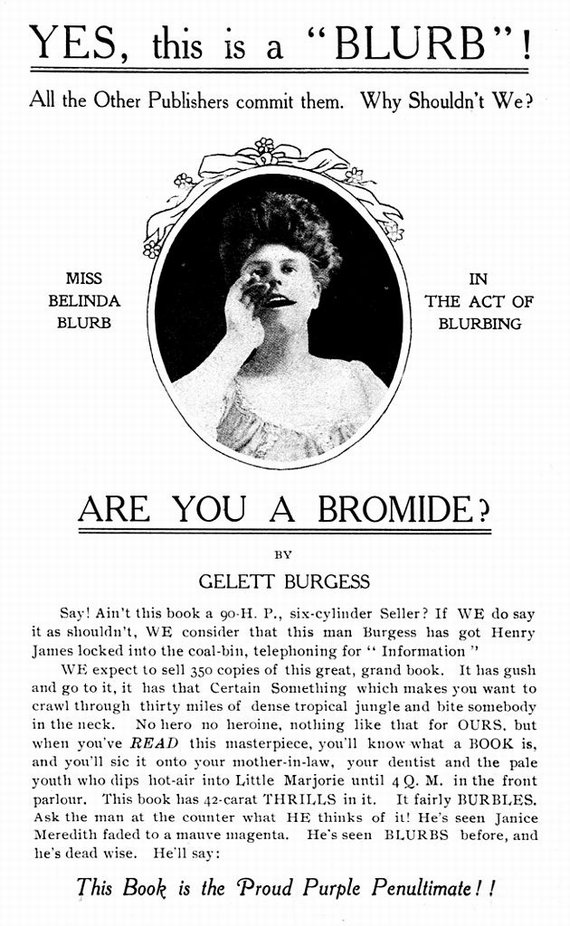

When did this circus get started? It’s tempting to look back no further than the origins of the word “blurb,” coined in 1906 by children’s book author and civil disobedient Gelett Burgess. But blurbs, like bullshit, existed long before the term coined to describe them (“bullshit,” in case you were wondering, appeared in 1915). They were born of marketing, authorial camaraderie, and a genuine obligation to the reader, three staples of the publishing industry since its earliest days, to which we will turn momentarily.

But before hunting for blurbs in the bookshops of antiquity, it’s important to get clear on what we’re looking for. Laura Miller at Salon writes: “The term ‘blurb’ is sometimes mistakenly used for the publisher-generated description printed on a book’s dust jacket — that’s actually the flap copy. ‘Blurb’ really only applies to bylined endorsements by other authors or cultural figures.” Miller can’t be completely right. For the consultants at Book Marketing Limited — and their numerous big-name clients — blurb describes any copy printed on a book, publisher-generated or otherwise, as evidenced by the criteria for the annual Best Blurb Award (ed note: as per the comment below, this is the typical British usage). So much for authorship. The term is often used of bylined endorsements that appear in advertisements. So much for physical location. And if we try to accommodate author blurbs, even Wikipedia’s “short summary accompanying a creative work” isn’t broad enough.

What a mess. In the interest of time I’m going to adopt an arbitrary hybrid definition — blurb: a short endorsement, author unspecified, that appears on a creative work. So Orwell’s example and Manning’s reviews would be disqualified if they didn’t appear on a book or DVD case, respectively. I’ll leave that legwork to someone else, because we’ve got serious ground to cover.

3.

If you needed beach reading in ancient Rome, you’d probably head down to the Argiletum or Vicus Sandaliarium, streets filled with booksellers roughly equivalent to London’s Paternoster Row. But how to know which books would make your soul shriek with delight? There was no Sunday Times; newspaper advertising didn’t catch on for another 1,700 years, and neither did professional book reviewers. Aside from word of mouth, references in other books, and occasional public readings, browsers appear to have been on their own.

Almost. Evidence suggests that booksellers advertised on pillars near their shops, where one might see new titles by famous people like Martial, the inventor of the epigram (nice one, Martial). It’s safe to assume that even in the pre-codex days of papyrus scrolls, a good way to assess the potential merits of Martial’s book would have been to read the first page or two, an ideal place for authors to insert some prefatory puff. Martial begins his most well-known collection with a note to the reader: “I trust that, in these little books of mine, I have observed such self-control, that whoever forms a fair judgment from his own mind can make no complaint of them.” Similar proto-blurbs were common, often doubling as dedications to powerful patrons or friends. The Latin poet Catullus: “To whom should I send this charming new little book / freshly polished with dry pumice? To you, Cornelius!” For those who weren’t the object of the dedication, these devices likely served the same purpose that blurbs do today: to market books, influence their interpretation, and assure prospective readers they kept good company.

Nearly fourteen hundred years passed before Renaissance humanists hit on the idea of printing commendatory material written by someone other than the author or publisher. (Or maybe they copied Egyptian authors and booksellers, who were soliciting longer poems of praise (taqriz) from big-shot friends in the 1300s.) By 1516, the year Thomas More published Utopia, the practice was widespread, but More took it to another level. He drew up the blueprint for blurbing as we know it, imploring his good friend Erasmus to make sure the book “be handsomely set off with the highest of recommendations, if possible, from several people, both intellectuals and distinguished statesmen.” This it was, by a number of letters including one from Erasmus (“All the learned unanimously subscribe to my opinion, and esteem even more highly than I the divine wit of this man…”), and a poem by David Manning’s more eloquent predecessor, a poet laureate named “Anemolius” who praises Utopia as having made Plato’s “empty words… live anew.” What would he have written about The Patriot?

Nearly fourteen hundred years passed before Renaissance humanists hit on the idea of printing commendatory material written by someone other than the author or publisher. (Or maybe they copied Egyptian authors and booksellers, who were soliciting longer poems of praise (taqriz) from big-shot friends in the 1300s.) By 1516, the year Thomas More published Utopia, the practice was widespread, but More took it to another level. He drew up the blueprint for blurbing as we know it, imploring his good friend Erasmus to make sure the book “be handsomely set off with the highest of recommendations, if possible, from several people, both intellectuals and distinguished statesmen.” This it was, by a number of letters including one from Erasmus (“All the learned unanimously subscribe to my opinion, and esteem even more highly than I the divine wit of this man…”), and a poem by David Manning’s more eloquent predecessor, a poet laureate named “Anemolius” who praises Utopia as having made Plato’s “empty words… live anew.” What would he have written about The Patriot?

Hyperbole, fakery, shameless cronyism: though it will be another three hundred years before blurbs make their way onto the outside of a book, things are looking downright modern. In the 1600s practically everyone wrote commendatory verses, some of which were quite beautiful, like Ben Jonson’s for Shakespeare’s First Folio: “Shine forth, thou Star of Poets, and with rage / Or influence, chide or cheer the drooping stage, / Which, since thy flight from hence, hath mourned like night, / And despairs day, but for thy volume’s light.” (Interestingly, Shakespeare himself never wrote any — one can only imagine what a good blurb from the Bard would have done for sales.)

It was only a matter of time before things got out of control. The advent of periodicals in the early 18th century facilitated printing and distribution of book reviews, and authors and publishers wasted no time appropriating this new form of publicity. Perhaps the best example is Samuel Richardson’s wildly successful Pamela, an epistolary novel about a young girl who wins the day through guarding her virginity. Richardson made excellent use of prefatory puff, opening his book with two long reviews: the first by French translator Jean Baptiste de Freval, the second unsigned but likely written by Rev. William Webster, which first appeared as pre-publication praise in the Weekly Miscellany, one of Britain’s earliest periodicals.

It was only a matter of time before things got out of control. The advent of periodicals in the early 18th century facilitated printing and distribution of book reviews, and authors and publishers wasted no time appropriating this new form of publicity. Perhaps the best example is Samuel Richardson’s wildly successful Pamela, an epistolary novel about a young girl who wins the day through guarding her virginity. Richardson made excellent use of prefatory puff, opening his book with two long reviews: the first by French translator Jean Baptiste de Freval, the second unsigned but likely written by Rev. William Webster, which first appeared as pre-publication praise in the Weekly Miscellany, one of Britain’s earliest periodicals.

Hyperbole? “This little Book will infallibly be looked upon as the hitherto much-wanted Standard or Pattern for this kind of writing”; “The Honour of Pamela’s Sex demands Pamela at your Hands, to shew the World an Heroine, almost beyond example…”

Fakery? The book also had a preface by the “editor,” really Richardson himself, which concluded a laundry list of extravagant praise with the following: “…An editor may reasonably be supposed to judge with an Impartiality which is rarely to be met with in an Author towards his own Works.”

Shameless cronyism? De Freval was in debt to Richardson when he wrote his review, as was Rev. Webster, whose Weekly Miscellany was funded partially by Richardson.

All of this sent Henry Fielding over the edge. Nauseated as much by the ridiculous blurbs as the content of the novel, Fielding wrote a satirical response entitled Shamela, which he prefaced with a note from the editor to “himself,” a commendatory letter from “John Puff, Esq.,” and an exasperated coda: “Note, Reader, several other COMMENDATORY LETTERS and COPIES of VERSES will be prepared against the NEXT EDITION.”

All of this sent Henry Fielding over the edge. Nauseated as much by the ridiculous blurbs as the content of the novel, Fielding wrote a satirical response entitled Shamela, which he prefaced with a note from the editor to “himself,” a commendatory letter from “John Puff, Esq.,” and an exasperated coda: “Note, Reader, several other COMMENDATORY LETTERS and COPIES of VERSES will be prepared against the NEXT EDITION.”

While Fielding may have been the first to parody blurbs, it was another literary giant who truly modernized them. A master of self-promotion, Walt Whitman knew exactly what to do when he received a letter of praise from Ralph Waldo Emerson. The second edition of Leaves of Grass is, as far as I know, the first example of a blurb printed on the outside of a book, in this case in gilt letters at the base of the spine: “I Greet You at the Beginning of a Great Career / R W Emerson.” (Emerson’s letter appeared in its entirety at the end of the book along with several other reviews — three of which were written by Whitman — in a section entitled “Leaves-Droppings.”)

Whitman’s move wasn’t completely unprecedented. The earliest dust jacket in existence (1830) boasts an anonymous poem of praise on the cover, and printers had long been in the habit of putting their device at the base of the spine. Nevertheless, the impulse to combine them with a bylined review was sheer genius, and Emerson’s blurb can be read as greeting not only Whitman, but also the great career of its own updated form.

4.

After Whitman there were further innovations. A century ago, fantasy author James Branch Cabell (unsung favorite of Mark Twain and Neil Gaiman) prefigured self-deprecators like Chris Ware by including negative blurbs at the back of his books: “The author fails of making his dull characters humanely pitiable. New York Post.” Or, as Ware put it on the cover of the first issue of Acme Novelty Library: “An Indefensible Attempt to Justify the Despair of Those Who Have Never Known Real Tragedy.” Unlike Cabell’s, Ware’s first negative blurb was self-authored, but those featured on Jimmy Corrigan were not. Marvel Comics followed suit when it issued its new “Defenders.” (A related strategy — Martin Amis’ The Information was stickered “Not Booker Prize Shortlisted.”)

After Whitman there were further innovations. A century ago, fantasy author James Branch Cabell (unsung favorite of Mark Twain and Neil Gaiman) prefigured self-deprecators like Chris Ware by including negative blurbs at the back of his books: “The author fails of making his dull characters humanely pitiable. New York Post.” Or, as Ware put it on the cover of the first issue of Acme Novelty Library: “An Indefensible Attempt to Justify the Despair of Those Who Have Never Known Real Tragedy.” Unlike Cabell’s, Ware’s first negative blurb was self-authored, but those featured on Jimmy Corrigan were not. Marvel Comics followed suit when it issued its new “Defenders.” (A related strategy — Martin Amis’ The Information was stickered “Not Booker Prize Shortlisted.”)

These satirical strategies highlight the increasingly common suspicion, nascent in Fielding’s parody of Richardson, that blurbs just aren’t meaningful. Publishers, however, have evidently concluded that blurbs may not be meaningful, but they sure help move merchandise. Witness the advent of two recent innovations in paperback design: the blap and the blover (rhymes with cover).

The blap is a glossy page covered in blurbs that immediately follows the front cover. In deference to its importance, the width of the cover is usually reduced, tempting potential readers with a glimpse of the blap, and perhaps even accommodating a conveniently placed blurb that runs along the length of the book.

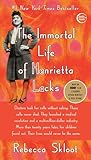

The blover is essentially a blap on steroids, literally a second book cover, made from the same cardstock, that serves solely as a billboard for blurbs. Blovers are not yet widespread, but given the ubiquity of blaps it is only a matter of time. (For an extreme case see The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, where the blover’s edge sports a vertical banality from Entertainment Weekly — “I couldn’t put the book down.” — not to mention the 56 blurbs on the pages that follow.)

The blover is essentially a blap on steroids, literally a second book cover, made from the same cardstock, that serves solely as a billboard for blurbs. Blovers are not yet widespread, but given the ubiquity of blaps it is only a matter of time. (For an extreme case see The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, where the blover’s edge sports a vertical banality from Entertainment Weekly — “I couldn’t put the book down.” — not to mention the 56 blurbs on the pages that follow.)

Blovers and blaps… what next? For my part, I can see where Orwell, Paglia, and Miller are coming from, and I certainly wouldn’t bemoan the disappearance of blurbs. But not everyone is like me. Some people enjoy glancing at reviews, or choosing a book based on the endorsements of their favorite authors. Blurbs sell books (maybe), and they allow established writers to help out the newbies. Those are good things. And since regulating them is as unfeasible as banning reviews, as long as blovers don’t replace covers I guess blurbs are a genre I can live with. And who knows — one day Murderer’s Row might be batting for me.

Previously: To Blurb or Not to Blurb

Image credit: wikimedia commons